Here’s a recap of the short video (see it above) and my takeaway for Elul.

Chaim Ginz is a scribe in Bnei Brak who had lost a young daughter to illness. After the Lag B’Omer tragedy of 2021, he was moved to visit the mourning families. Perhaps, he thought, my experience of loss could strengthen others.

He visited the Zekbach family whose 24 year old Menachem died in Meron. At the Shiva house, the family gave out Blessing After a Meal pamphlets because Menachem had from a young age been a tireless advocate for reciting those blessings carefully, from a written text, rather than by heart. Chaim Ginz was moved. For the elevation of Menachem’s soul, he accepted this upon himself.

About a month later, Chaim finished a writing project and was looking for additional work. The writing samples he brought to others were met with a lukewarm response: “They’re nice but they don’t stand out.” He felt discouraged.

Alone one day at a workspace for scribes, he finished his meal and was about to recite his blessings by heart when he remembered Menachem Zekbach, obm. He looked around the workspace for a printed blessing. He couldn’t find. He looked again. And again. After 10 minutes of searching he finally found a peculiar pamphlet: it was an entire text of the Blessing After a Meal written in an exquisite version of the font that scribes write in. He said his blessings from the pamphlet and thought: maybe this sample is the inspiration that will improve my work.

He spent three hours carefully writing in scribe style the text of the Blessing After a Meal, inspired by text he’d just used. Five minutes after finishing, he got a call from a fellow scribe.

“I was offered to write a Sefer Torah and I’m too busy. Do you want the job? If so, bring me a sample of your writing.”

Chaim brought the newly inspired parchment he’d just written to the address his friend gave him. A half hour later he got another call. “They love your work. You’re hired.”

“Who’s commissioning this sefer Torah?” asked Chaim.

“A very special Jew in Brooklyn is dedicating a Torah to each of those lost at Meron.”

“Which family will I write for?” asked Chaim.

“You’re writing for the Zekbachs.”

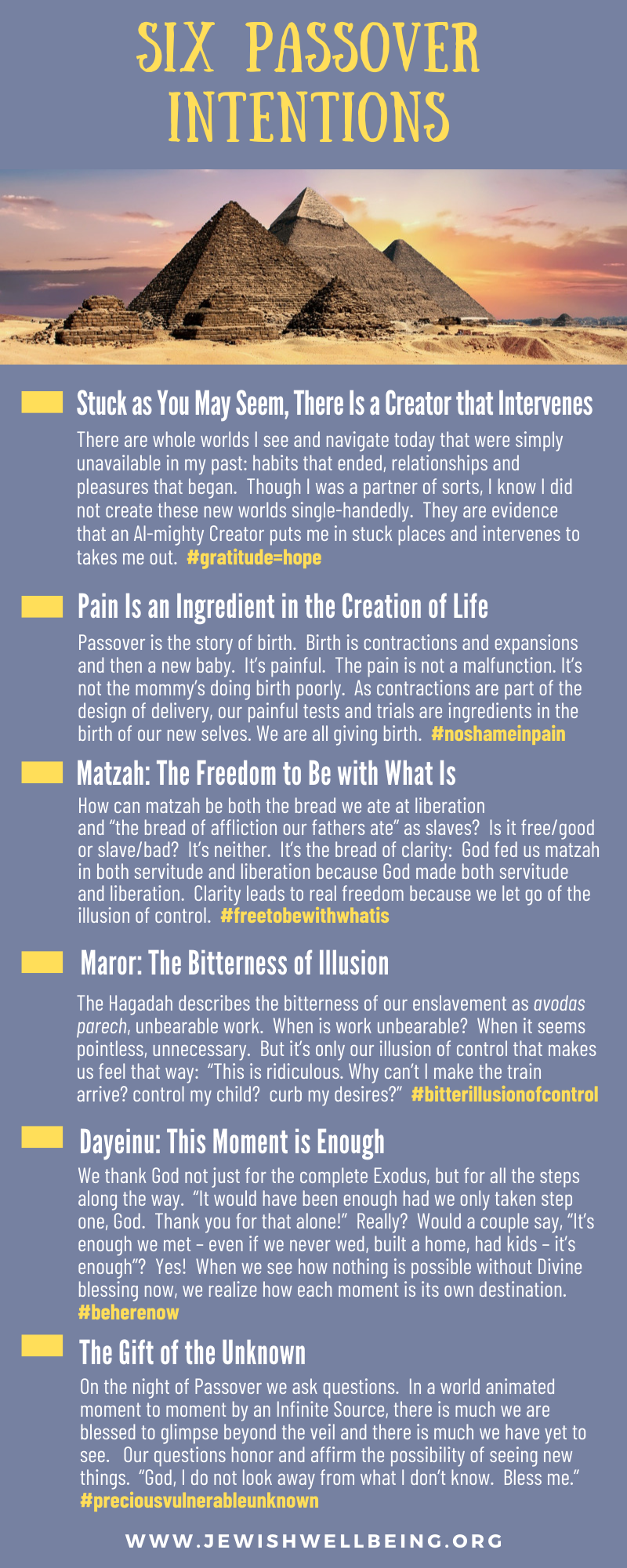

Here’s the Elul message I feel emblazoned on my heart from this story. Elul is the Jewish name of the month that precedes Rosh Hashana. It’s a month of preparation before the awesome days of Jewish New Year and Yom Kippur.

It’s also an acronym for a verse from Song of Songs in which the Jewish people say to God: “I am to my Beloved, and my Beloved is to me.” This signifies the step a Jew takes to initiate a relationship with God, and the promise that God will show him His desire for relationship in turn. God’s blessing is everywhere in our lives. When we show our desire to connect, that blessing will become even more obvious.

At so many points, Chaim Ginz took a step toward God.

He initiated sharing his experience of loss with mourning families.

He accepted to bless from a written text as a merit to Menachem Zekbach, obm.

He stood firm in that commitment despite both inconvenience and his discouraged state of mind.

He acted on his inspiration to improve his writing – for three hours.

And then he was gifted from Above with the opportunity to further elevate the soul of Menachem Zekbach while simultaneously elevating his career.

We are regularly hearing the whispers of our heart to act. Often those whispers are invites from God. What better time than Elul to step toward the invitation?

RSS Feed

RSS Feed